The Relevance of Playing in 12 Keys to Both Jazz and Non-Jazz Musicians

During the 1940s, the Bebop Era in jazz history, virtuosity became an important and necessary part of being a jazz musician. Charlie Parker, Dizzy Gillespie, and their contemporaries started the trend of learning tunes such as the blues, rhythm changes, and “Cherokee” in all 12 keys. This has become ingrained in the tradition of jazz. Today, it can be a rite of passage for a young jazz musician. Consider the following scenario, a very common scenario: a young jazz musician walks up to the bandstand during a jam session and calls a tune he or she is extremely familiar with, and has been practicing hard. The veteran jazz musician behind him or her calmly says something along the lines of, “okay, let’s play it in the key of __.” The young musician is thrown for a loop, because he only learned the song in one key. It may seem like an unfair rite of passage, but it is a skill that is needed to be a true jazz musician. Singers are constantly singing songs not in their original key. The voice is a personal instrument and each singer’s vocal range varies from person to person. Playing the saxophone, or any instrument that offers more flexibility than the voice, requires us to be more flexible ourselves.

During the 1940s, the Bebop Era in jazz history, virtuosity became an important and necessary part of being a jazz musician. Charlie Parker, Dizzy Gillespie, and their contemporaries started the trend of learning tunes such as the blues, rhythm changes, and “Cherokee” in all 12 keys. This has become ingrained in the tradition of jazz. Today, it can be a rite of passage for a young jazz musician. Consider the following scenario, a very common scenario: a young jazz musician walks up to the bandstand during a jam session and calls a tune he or she is extremely familiar with, and has been practicing hard. The veteran jazz musician behind him or her calmly says something along the lines of, “okay, let’s play it in the key of __.” The young musician is thrown for a loop, because he only learned the song in one key. It may seem like an unfair rite of passage, but it is a skill that is needed to be a true jazz musician. Singers are constantly singing songs not in their original key. The voice is a personal instrument and each singer’s vocal range varies from person to person. Playing the saxophone, or any instrument that offers more flexibility than the voice, requires us to be more flexible ourselves.

Playing in 12 keys is not only relevant to the jazz musician. I am a jazz musician, but I end up playing many non-jazz gigs. I regularly play Top 40 gigs. These include weddings, private parties, corporate events, etc. I sat in with a wedding band last November. Their song list was mostly pop songs that I had played hundreds of times before. But, they decided for some reason to play everything down a half step. I’m not sure why. Maybe it fit the vocal range of the singers slightly better? Now, the drummer didn’t need to transpose, the guitar players tuned their guitars down a half step, as did the bass player, and the keyboard player could program his keyboard to play down a half step automatically. As the only pitched, acoustic instrument in the band, I was not able to tune my saxophone down a half step. It was the knowledge, ability, and experience I have playing in 12 keys that allowed me to succeed on that gig. Point being: even if you’re not a jazz musician, the information provided in this blog is still useful and relevant.

Basic Jazz Exercises for the Saxophone

The prospect of being able to play comfortably in all 12 keys at a high level can be extremely intimidating. Having a step-by-step systematic approach can make it less so. A logical and necessary first step is to feel comfortable playing all of your major scales. When I started studying saxophone privately back in the seventh grade, my teacher would have me run through all my major scales at the beginning of each lesson. If I wanted to spend my lesson time on other, more fun things, I had to be able to get through my scales quickly and accurately. Feeling comfortable playing all of your scales is necessary and fundamental, and is a prerequisite to practicing the material I’m going to lay out in this blog.

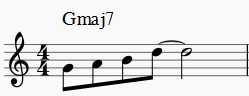

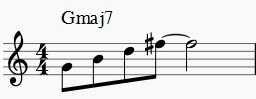

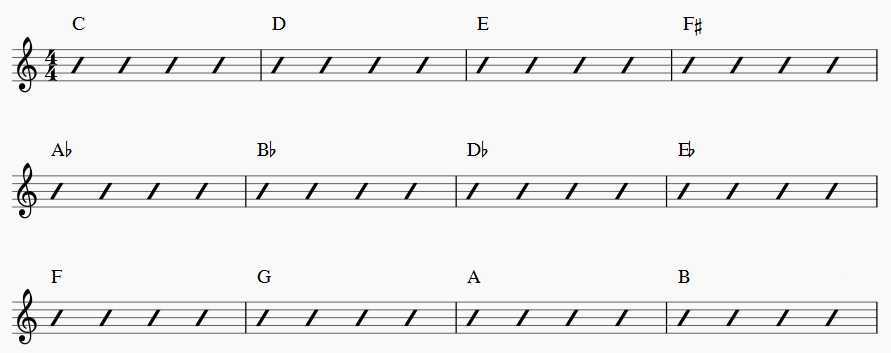

Once you have your major scales down, what are some other basic exercises that can be practiced? Taking a few notes from a scale and practicing them in 12 keys can be less daunting and more practical in application. You would never play a C major scale in it’s entirely when you see a C major chord in a progression while improvising. We can break the major scale down into smaller sections. The following jazz exercises for the saxophone are just a couple of examples of four-note groups that are useful in practice as well as in application:

These are just a couple of examples of four-note groups. There are many, many more permutations that can be figured out and practiced. The first example above can be practiced in all its permutations: 1235, 1253, 1325, 1352, 1523, 1532, etc. The second example can also be practiced in all its permutations: 1357, 1375, 1537, 1573, 1735, 1753, etc. These are all the permutations of the above examples that start on the root. This is a good place to begin, but ultimately it will sound better to start on the third, the fifth, or the seventh.

The above examples are derived from the major scale. These four-note groups can be applied to any and every scale: major, minor, Dorian, Mixolydian, diminished, whole tone, etc.

The above examples also only illustrate one possible rhythm. You should try using different rhythms to create interest.

Methods for Practicing the Basic Jazz Exercises in 12 Keys

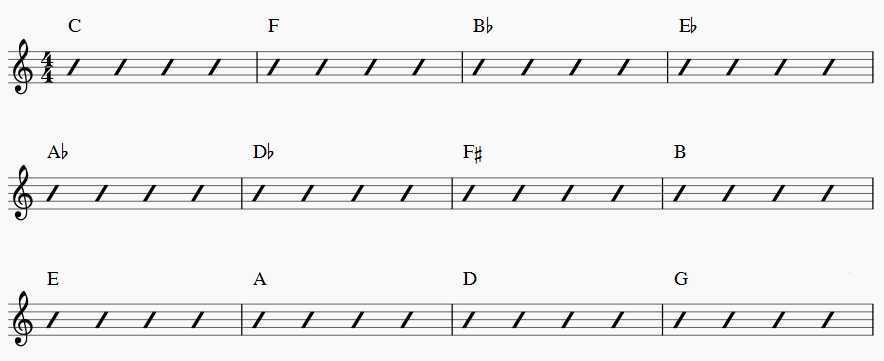

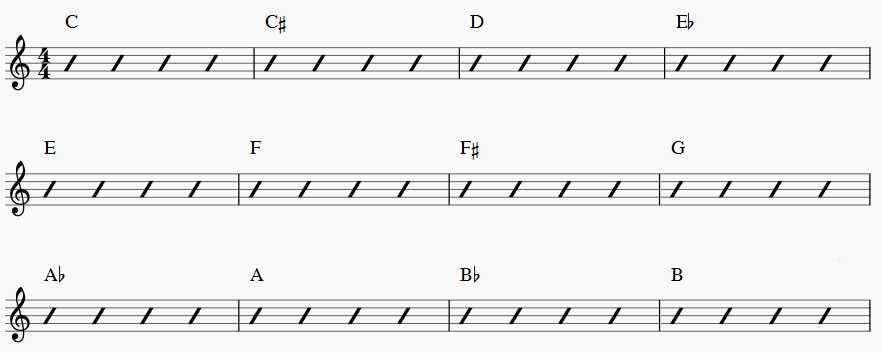

So, how do you go about practicing these basic jazz exercises for the saxophone in all 12 keys? There are several ways to run through all the keys. Jazz musicians practice exercises in different root movements. This means that they practice using different progressions, or different ways of getting through all 12 keys. Here are a few root movements that jazz musicians use to practice exercises in 12 keys:

The above examples are just a few examples of root movements. In addition to the cycle of fourths, half steps, and whole steps, you can also move by the cycle of fifths, up a fourth and down a tritone, etc. Try to find other root movements that get through all 12 keys.

Variance is important. If you always practice using the same root movement, then you might get used to only playing in that root movement. You want to vary it so that you’re constantly challenging yourself. Also keep in mind, if you always practice in the cycle of fourths, you’re missing a lot of the range of the saxophone. When you practice in half steps, you want to start from the lowest possible note on the horn (low Bb) and play the exercises ascending all the way up to the highest note on the horn (sky’s the limit).

How to Apply to Jazz Tunes

Once you learn these jazz exercises for the saxophone, and can run them through different root movements, how do you turn them into a practical application for performing jazz and improvising? You can begin by applying them to tunes. Here is an example of how you can apply the first jazz exercise to a very basic blues progression:

Running through basic jazz exercises for the saxophone on a tune may sound uncreative, unoriginal, and frankly, boring. But, this is the way improvising begins. As you learn more complicated exercises, your playing will begin to sound better and better. Even professional jazz musicians run exercises through tunes. Not only does it help to solidify the exercise, but it also helps to learn the tune.

The Benefits of Being Comfortable in 12 Keys

There are an infinite number of jazz exercises for the saxophone. At a certain point, you just have to pick and choose what sounds good to you. It is impossible to learn everything. There’s no way you could master an instrument or a concept, and that’s what makes jazz such a rewarding experience; it’s a lifelong learning process. Jazz is about individuality, originality, uniqueness, progressive thinking.

Learning jazz exercises for the saxophone in 12 keys is a necessary part of becoming a successful jazz musician. The above examples are uninspired, but they are the first step of a step-by-step systematic approach that will ultimately lead to success as a jazz improviser and a musician. Once you learn the above examples and feel comfortable applying them, you can move on to more complicated exercises, which I will illustrate in future blogs.