Another Real Life Example of Playing in 12 Keys

In my last blog, I referenced a couple of instances of real life playing situations where you need to be able to play in 12 keys. In the first example, I talked about how playing in 12 keys is so rooted in jazz, whether as a rite of passage from jazz veterans to young jazz musicians or as a necessity for playing with singers in any genre. The second example was a real life experience of mine that involved playing in a wedding band where they expected me to play a four hour gig of pop songs a half step below the original recordings’ keys.

Another instance came up in my life recently where I was expected to be able to play equally and comfortably in 12 keys. I recently started playing saxophone at an urban gospel church in Brooklyn, New York. Contemporary gospel music has many interesting attributes, one of them being the constant modulations. It’s not unusual for a song to change keys three, four, or more times. The most common modulation is going up by a half step. Gospel music is a direct application of the digital patterns we worked on last time. Playing pop music isn’t incredibly complicated. You’re not taking chromatic lines through the keys; in pop music, you’re playing simple pentatonic and blues-based lines. Take, for example, the digital pattern 356 up to 1. I’m sure this sounds very familiar to you. It is one of the most common horn lines in pop music. So, it would be beneficial for you to learn to play it through all of the keys.

Another quick example of real life application is playing with blues bands or other guitar-centered groups. Non-jazz guitar players love open strings. Those open strings are E A D and G. So, those are the keys guitar players feel most comfortable playing in. Unfortunately, on saxophone those keys transpose to C# F# B E (Eb horns) and F# B E A (Bb horns). In this situation, you better feel as comfortable playing in C# as you do playing in C.

Brief Review from Part I

Before you read on, if you haven’t read the first installment of this blog series entitled “Jazz Exercises for the Saxophone: An Introduction to Playing in 12 Keys”, I highly suggest you take the time to read it before reading this one, as each successive post will build on the one before it.

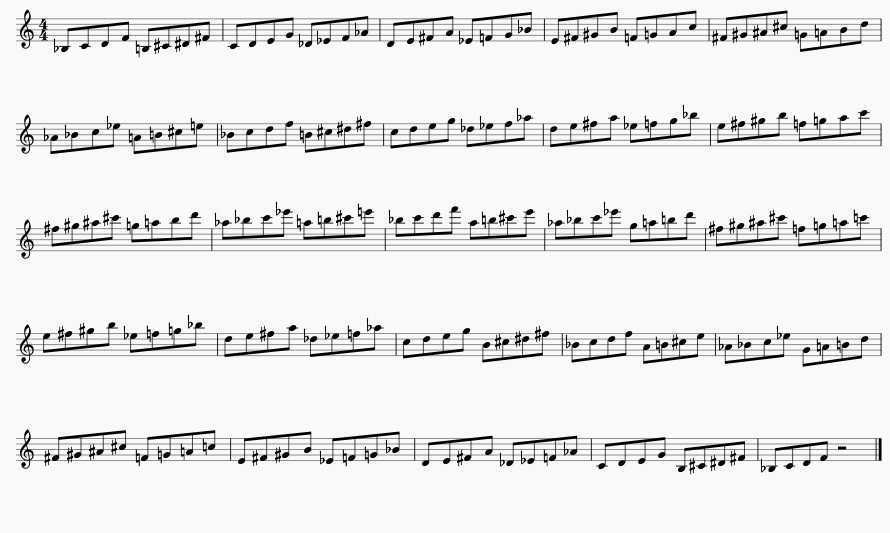

Let’s start with a couple of warm-up exercises to make sure you properly digested the material from the first post. For the first example, I’ve taken the time to write out 1235 in half steps throughout the entire range of the saxophone to stress the importance of practicing these exercises in all possible registers.

Next, I’ve written out an exercise to practice the application of digital patterns to real life jazz situations. Last time we used a basic blues progression, so this time we’ll use a popular jazz standard for application practice. We’ll take the ‘A’ section from “Autumn Leaves” and apply the 1357 digital pattern exercise over it. I’ve written it out in both Eb for alto and bari saxophone (first line) and Bb for tenor and soprano saxophone (second line).

After playing through the example provided, try to apply some other digital patterns. It would be beneficial to work through all the permutations of 1357: 1357, 1375, 1537, 1573, 1735, 1753, 3157, 3175, 3517, 3571, 3715, 3751, etc. In addition to these, you could use the 1235 digital patter in all of its permutations.

Chords vs. Progressions

When I was a young musician, I tried desperately to figure out jazz on my own. I had an interest in jazz and I definitely had the required discipline (and then some), but I couldn’t find a jazz saxophone teacher in my area. I had the desire to learn, but I didn’t have the tools. Jazz is often a process of trial and error, but it does help to have an instructor to guide you in the right direction.

One of my biggest problems was seeing each chord as its own entity. This is a problem for many reasons. It makes things more complicated than they have to be. Imagine reading a sentence and  seeing each word as its own thing, not related to the word that comes before it or after it. This process would make reading very labor intensive and time consuming. It would essentially mean you have a great understanding of vocabulary while having virtually no understanding of syntax. This leads to making things sound unnatural. I’ll explain this more later in the article.

seeing each word as its own thing, not related to the word that comes before it or after it. This process would make reading very labor intensive and time consuming. It would essentially mean you have a great understanding of vocabulary while having virtually no understanding of syntax. This leads to making things sound unnatural. I’ll explain this more later in the article.

Jazz musicians often have a great understanding of Music Theory, particularly in relation to harmony. Each chord is not its own entity; chords are not isolated or random. There are pre-dominants, dominants, and tonics. Jazz musicians understand this because they have to. This is a necessary part of being a great improviser.

With the digital pattern exercises, we were treating each chord as its own thing. Practicing digital patterns can feel like a tedious process and doesn’t sound very inspiring or interesting, but it’s a necessary first step. You need some understanding of vocabulary before you can begin to understand syntax. After understanding each chord on its own, connecting chords to create progressions is the next step.

The ii-V-I Progression

The ii-V-I progression is the most important progression in traditional jazz. Other jazz educators might think I’m crazy for making it a subheading in one installment of a series of blog posts. I could write a series completely on the ii-V-I progression. That’s how important it is. In fact, there are already thousands of method books, articles, videos, etc. that talk about the ii-V-I progression in detail. I suggest you seek out some of these valuable resources. However, for the purpose of the content of this blog, I believe this section is enough. But, I’m just letting you know how important it is.

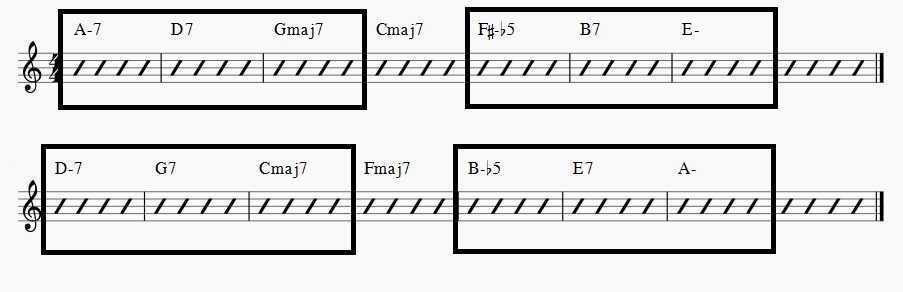

In the example below, I’ve put a box around every time the ii-V-I progression happens in the ‘A’ section of “Autumn Leaves”.

“Autumn Leaves” illustrates both the ii-V-I in major and the iib5-V-i in minor. I’ve used “Autumn Leaves” as the example for continuity’s sake. I recommend opening up a Real Book or looking at some jazz lead sheets you have and looking for the ii-V-I progression. You might be surprised how often it occurs. It’s a major building block of many jazz standards. The ii-V-I is the syntax in the metaphor from earlier. The ii, the V, and the I are each the words that make up the ii-V-I sentence.

Common Resolutions

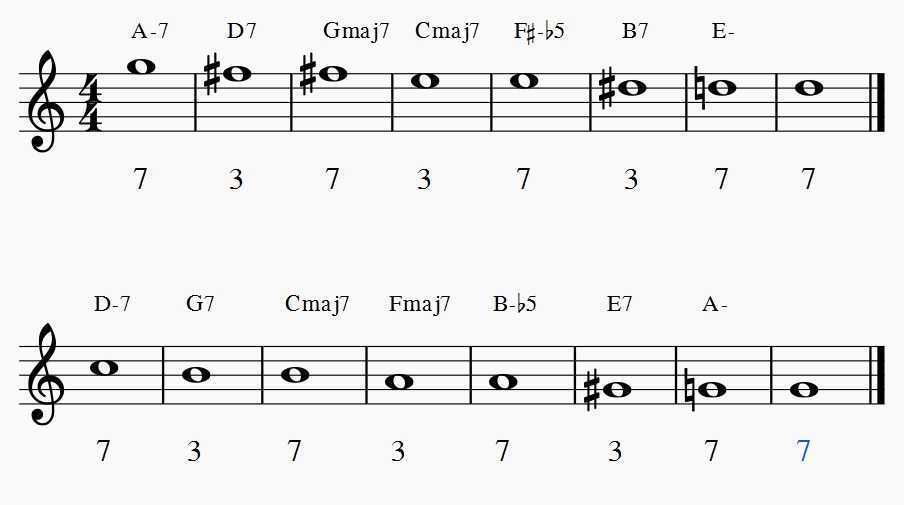

Now that you understand a little bit about chords vs. progressions, how can you make your improvising begin to sound a little more natural? One reason the digital patterns sound so unnatural is because there’s no connection between the chords; you’re treating each chord as its own entity. You play 1235 on one chord and then leap to 1235 on the next chord. It’s much more pleasing to the ear to connect to the next chord via half or whole step. There are many common resolutions, the most common being 7-3 and 3-7. In the example below, I’ve illustrated both of these resolutions. Notice how there is very little movement and no leaps between notes, as there were with the digital patterns. It may not sound interesting on its own. If you can either get someone to play the chords on the piano or find a play-along of “Autumn Leaves”, this exercise will be much more effective. With the chords, this example is much more pleasing to the ear than the digital patterns.

The 3-7 and 7-3 resolutions are the most common, but there are plenty of other examples. Some other examples that fit over the ii-V-I progression include 5-b9-5, 5-#9-7, 9-#5-7, etc. Once you’ve figured out the 3-7 and 7-3 resolutions over the ii-V-I progression in all 12 keys, try figuring out some other ones and see what sounds good to your ears.

Combining Digital Patterns and Common Resolutions

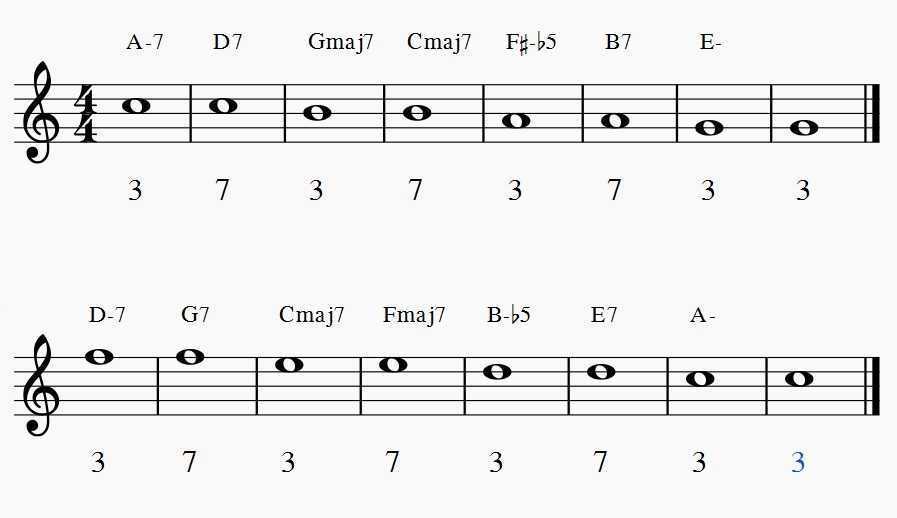

So, we’ve discussed how boring and unnatural digital patterns sound. We’ve also talked about how the common resolutions sound good but are too slow moving to be interesting as the sole base of an improvised solo. So what am I teaching you here? How to be a boring improviser? How to be a boring jazz musician? Well, here’s where this stuff begins to pay off. We’ve got all the permutations of digital patterns and we understand how to connect chords via common resolutions. When we combine these two, things start to come together. The following example demonstrates this over “Autumn Leaves” once again.

In this example, we’re using digital patterns in multiple permutations, so it doesn’t sound monotonous. We’re connecting chords via half or whole step, which creates interest and makes it sound like we’re going somewhere, rather than just playing isolated patterns. We’re moving in quarter notes, so it doesn’t sound so slow moving. Sure, it might sound more like a simple bass line than a jazz saxophone player’s improvisation, but it requires a competent understanding of theory and harmony. These jazz exercises are purely exercises in harmony. Try playing the above example, but altering the rhythm. This creates a little more interest, and could potentially make for a good solo.

Summary of Part II

The first installment of my blog series “Jazz Exercises for the Saxophone” discussed the importance of 12 keys and provided the beginning of a systematic approach for learning to feel comfortable playing in every key. This second installment presented some new information that, when combined with the material from the previous lesson, can begin to make you feel comfortable playing over jazz standards.

We learned about the ii-V-I progression and how to begin to approach it. I briefly mentioned flipping through the pages of a Real Book and searching for the ii-V-I progression wherever you can find it (which will be many places). I highly recommend using the digital patterns, the common resolutions, and a combination of these two approaches over several jazz standards. For starters, I recommend playing over the blues, any rhythm changes (“I Got Rhythm”), “Autumn Leaves”, “How High the Moon”, “Solar”, and, if you’re looking for a challenge, “Cherokee”. These tunes are filled with ii-V-Is. “Cherokee” hits seven keys in one song.

Another way to practice the digital patterns and common resolutions over the ii-V-I progression is to run through the ii-V-I progression in 12 keys. Remember, the point of this blog series is to have you end up feeling comfortable playing through all the keys. You can practice this by using the root movements, as discussed in the last lesson (cycle, whole steps, half steps, minor 3rds, etc.) As an exercise, write out the ii-V-I in all the keys, in different root movements, so you have a visual while practicing. Ultimately, the ii-V-I progression should just be inherent in your mind.

Another way to practice the digital patterns and common resolutions over the ii-V-I progression is to run through the ii-V-I progression in 12 keys. Remember, the point of this blog series is to have you end up feeling comfortable playing through all the keys. You can practice this by using the root movements, as discussed in the last lesson (cycle, whole steps, half steps, minor 3rds, etc.) As an exercise, write out the ii-V-I in all the keys, in different root movements, so you have a visual while practicing. Ultimately, the ii-V-I progression should just be inherent in your mind.

Take the time to really digest all the information provided above. It’s a lot of information. There are no shortcuts in learning jazz, learning to improvise, learning to play in 12 keys. I’m trying to guide you in the right direction, but this stuff takes hours and hours of practice. I suggest finding a private teacher to assist you and make sure you’re understanding each successive lesson before moving on to the next. It also helps to have someone else play the examples for you, or with you, or play the respective chords on the piano. Jazz is an aural tradition. Ear training should be part of your daily practice. I’m available in the New York City area as well as for online lessons. Good luck practicing.