The Altered Scale

When we listen to, study, or discuss music from a compositional or improvisational standpoint, we frequently talk about a technique called “tension and release”. What this refers to is a method for developing variation in music. It’s an approach to create interest in order to prevent a piece of music, or an improvised solo, from potential monotony; to keep music from being boring.

“Tension and release” can be applied to music melodically, harmonically, and rhythmically. A few examples of variation, or polarities, that create “tension and release” are: loud vs. soft (dynamics), high vs. low (range), dense vs. sparse, consonance vs. dissonance, etc. Consonance vs. dissonance is the most effective way to develop harmonic “tension and release”. For the specific purpose of this article, we’ll focus on harmonic “tension and release”.

The most common place to use harmonic “tension and release” in music is on the V7-I resolution. The dominant chord is often used as a platform for dissonance before it resolves to the consonant tonic chord. In other words, the dominant chord is the “tension” and the tonic chord is the “release”.

How do we accomplish this? I hinted at it in the past couple of articles I wrote on scales. The dominant chord can be altered however you want. The more it is altered, the tenser it will sound. A V7 with no altered tones creates the least amount of tension. It still creates tension because it feels like it needs to resolve to the I chord, but the tension is minimal. To create a more tense sounding chord we could alter the V7 chord to be a V7(#11), V7(b9), V7(#9), V7(#5), etc.

How do we accomplish this? I hinted at it in the past couple of articles I wrote on scales. The dominant chord can be altered however you want. The more it is altered, the tenser it will sound. A V7 with no altered tones creates the least amount of tension. It still creates tension because it feels like it needs to resolve to the I chord, but the tension is minimal. To create a more tense sounding chord we could alter the V7 chord to be a V7(#11), V7(b9), V7(#9), V7(#5), etc.

We’ve learned a couple of the scales that correspond to the altered dominant chords. The diminished scale alters the ninth; the whole tone scale alters the fifth. There are also other ways to alter the dominant chord. You could use some common chord substitutions (tritone sub, minor third sub). Although, chord substitutions are really just a different means to get to the same end.

What if we combine the V7(#9) and the V7(#5) to get create even more tension? We get the V7(#9#5) chord or the V7alt. chord. Cue the altered scale.

The altered scale is the most dissonant sound you can apply to the dominant chord without sounding wrong (technically, holding out a major seventh or a perfect fourth on a dominant chord may be more dissonant, but they’re also not functional (as more than passing tones) and not in the tradition, making them sound completely “wrong”).

For reference, the altered scale is also sometimes referred to as the altered dominant scale or the diminished whole tone scale.

Scale Construction

Unlike the diminished scale and the whole tone scale, the altered scale is not a symmetric scale, so we can’t simply think of it intervallically; we have to figure out another way to analyze the scale. There are a couple of ways to think about the construction of the altered scale.

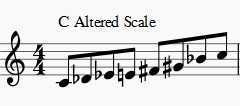

The altered scale is a dominant scale where all the non-defining chord tones are altered. The three essential notes that define any chord are the root, the third, and the seventh (dominant chord = root, major third, flat seventh). Any note that isn’t the root, the third, or the seventh can be altered. The diminished scale has altered ninths; the whole tone scale has altered fifths. In the altered scale, every note that isn’t the root, the third, or the seventh is altered. This leaves us with the root, the third, the flat seventh, both flat and sharp ninths, and both flat and sharp fifths (b5 is the same as #4/#11, #5 is the same as b13).

Using the same logic, you can also think of the altered scale as a combination of the diminished scale and the whole tone scale. The first half of the scale is the same as the diminished scale; the second half of the scale is the same as the whole tone scale. There is some overlap (the third and the sharp eleventh are in both the diminished and the whole tone scales).

Another way to think about the altered scale’s construction is to think of it in terms of modes. You may be familiar with the modes of the major scale: Ionian, Dorian, Phrygian, Lydian, Mixolydian, Aeolian, and Locrian. If not, it’s something worth looking into. The modes of the major scale are an important and widely studied part of music theory. In jazz, in addition to learning about the modes of the major scale, we also learn about the modes of the ascending melodic minor scale and the mode of the harmonic minor scale. The altered scale is the seventh mode of the ascending melodic minor scale. Simply put, the altered scale is the same scale as the ascending melodic minor scale, but starts on the seventh scale degree. If you know your melodic minor scales in twelve keys, you already know your altered scales in twelve keys.

Chord/Scale Relationship

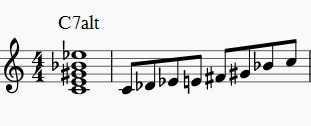

This section is going to be easy, since we already analyzed the altered scale above. The altered scale’s tones are: 1, b9, #9, 3, b5 (#4 or #11), #5 (b13), and b7. The altered scale works over any chord where both the ninth and fifth are altered in some way. Usually you’ll see something like C7alt. You could also see C7(#9#5), C7(b9b5), C7(#9b5), or C7(b9#5). Basically, any combination of altered fifths and ninths. These all signify the altered scale sound.

Scale Patterns

As per usual, you should practice the altered scale as you practice any other scale: in its full range, thirds, triads, etc. In addition, I’ve written out a few examples for you to practice in twelve keys:

The first two are pretty self-explanatory. The first example is just the scale in groups of four. The second example is the scale in descending triads.

The third example is based on a diminished scale exercise we went over a couple of articles back. It’s a little more complicated because there aren’t an even number of notes. Also, it has to be practiced in twelve keys since the altered scale isn’t a symmetric scale. I think it sounds pretty cool, though. It’s one that I use often when improvising.

Application to Improvisation

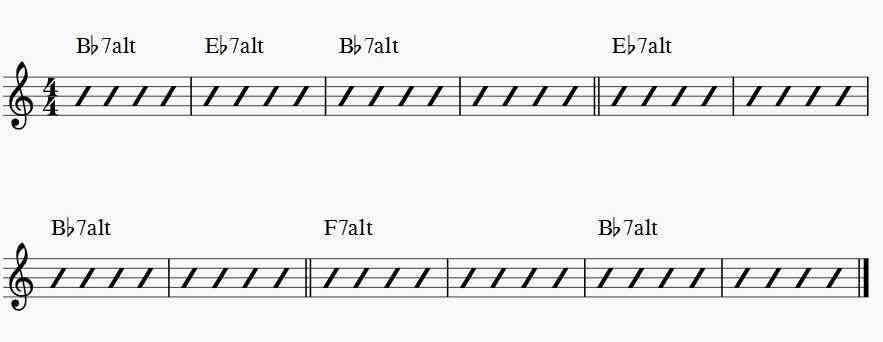

A concept that I introduced in the last article is using the blues as a tool for practicing and applying scales that alter the dominant chord. This is an effective practice method because the blues progression is both familiar and comprised of all dominant chords. It’s a quick and practical way to get your ear familiar with a new sound. A blues progression utilizing the altered scale would look something like:

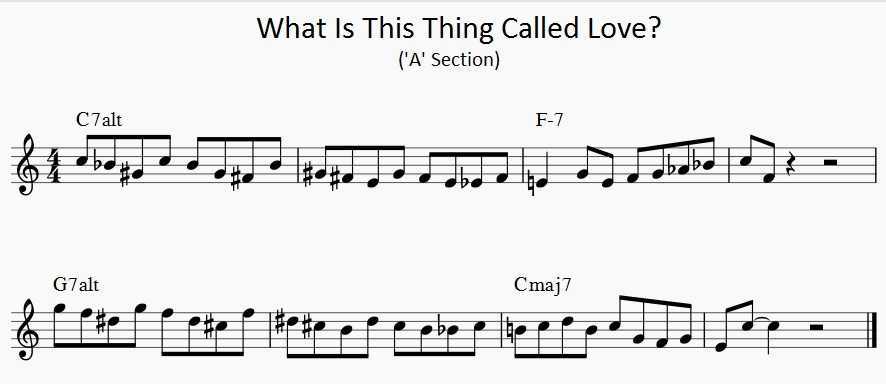

I’ve also written out an example that applies the altered scale to the standard “What Is This Thing Called Love?”:

In this example, I substituted the dominant chords with altered dominant chords (as opposed to the usual dominant with a flat or sharp ninth). This example uses one of the altered scale exercises from above and shows how it can be resolved to either a minor chord or a major chord.

Conclusion

There are a ton of resources about the diminished and whole tone scales. There are many public domain diminished and whole tone patterns. There aren’t nearly as many educational materials that discuss the altered scale. To me, this kind of makes practicing and using the altered scale more fun. Every jazz musician has the same diminished scale and whole tone scale vocabulary. You hear someone playing a diminished lick and you instantly recognize it, because you’ve spent countless hours practicing that same exact diminished lick yourself. I feel like there’s a lot more room for originality with the altered scale.

Now that we’ve learned the diminished scale, the whole tone scale, and the altered scale, it would be beneficial to practice them all side by side. Play a V7(#9) chord and run the diminished scale, then play a V7(#5) chord and run the whole tone scale, then play a V7(#9#5) chord and run the altered scale. It’s important to have the distinction between these three scales both under your fingers and in your ears. Any dominant chord can be altered however you like. If you clearly play the diminished sound, the rhythm section has the responsibility to alter the dominant chord with a flat or sharp ninth. In the same light, however, you have the responsibility to play the altered scale if the rhythm section chooses to alter the dominant chord with a sharp ninth and sharp fifth. These aren’t strict rules or anything. They just lead to a more fun musical experience. And ear training comes with time and experience. But, learning the distinction between altered dominant chord sounds is a big step in ear training and learning the jazz idiom.