If you happen to be a fan of classical music from the Impressionist Period on, then you’ve definitely heard the whole tone scale, at least passively. Not that the whole tone scale was never used before the late 19th century. You can hear it in music as far back as J.S. Bach, and probably even before then, but it started to become more widely used around the Impressionist Period.

Maybe classical music isn’t really your thing. Maybe you’re more a fan of pop music. Take a quick listen to Stevie Wonder’s “You Are the Sunshine of My Life”. You’ll hear the whole tone scale within the first ten seconds. It’s pretty easy to recognize.

In my last post, I talked about the diminished scale and how its possibilities of manipulation were seemingly endless to me. I talked about how learning about the diminished scale had a pretty big impact on my musical life. I’m not sure I can quite say the same thing about the whole tone scale. Maybe it’s just my ear’s personal preference, maybe it’s because there are less notes in the scale (and therefore, mathematically, less possible permutations), maybe it’s just not used as much as the diminished scale. It is, however, an important scale to know and a good preface to my next blog post’s scale (hint: it’ll be a combination of the diminished and whole tone scales). And it is definitely one that you’ll come across in jazz music.

Whole Tone Scale Construction

Last article, we learned what symmetric scales are. We talked about how the diminished scale is a part of this group. The whole tone scale is a symmetric scale as well. The whole tone scale’s repeating interval is the whole step; it’s comprised solely of whole steps.

The whole tone scale is easily recognizable for a few reasons. The interval between each note is the same. The only other scale like this is the chromatic scale. The whole tone scale is comprised completely of whole steps, like the chromatic scale is comprised completely of half steps. Because of this, if there is no underlying chord as a point of reference, it is impossible to tell what the root of the scale is. Also, since there are no half steps, there is no “leading tone” sound. The result of this sound (or lack of sound) is hard to put into words. I’ve heard people describe it as sort of “floating” sound. I can definitely hear that. Maybe it’ll sound different to you. The best way to know is to play it on a piano or your instrument and see what it connotes for you.

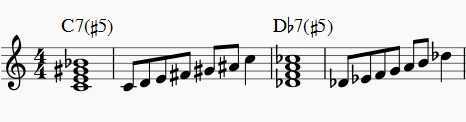

Because of the way the whole tone scale is constructed, there are only two possible whole tone scales. I’ve written out the C and Db whole tone scales. The D, E, F#, Ab, and Bb whole tone scales are the same as the C whole tone scale. The Eb, F, G, A, and B whole tone scales are the same as the Db whole tone scale. Practicing the whole tone scale is even easier than practicing the diminished scale. Once you know it in two keys, you can use it in all twelve keys.

Chord/Scale Relationship

Last blog post, I introduced the concept of “chord/scale relationships”. The best way to figure out how a scale relates to a chord is to break down the scale and analyze each tone. Before reading on, I advise that you look back at how the scale is constructed and try to figure out for yourself what chord the whole tone scale would sound good over.

The best way to learn and retain information is to learn the process of learning that information.

Okay, so hopefully you have a guess of what chord works with the whole tone scale. If we assign a scale degree to each note in the whole tone scale, we get 1, 9 (2), 3, #11 (#4), #5, and b7. If we stack these scale degrees to create a chord, we get 1, 3, #5, b7, 9, #11. So, the whole tone scale can be played over a dominant 7th or 9th chord with a sharp five and sharp eleven.

Occasionally, you’ll see an augmented triad (1, 3, #5). The whole tone scale works over this chord as well.

Scale Patterns

As I mentioned in the previous article, you should always practice all of your scales as you would practice your major scales. The whole tone scale is no exception. You should practice the whole tone scale full range, in thirds, in triads, etc. You should also figure out other ways to manipulate the scale to make it sound interesting.

Here are a few possibilities:

The first example is a basic scalar exercise you can use with any scale.

The second and third exercises are the whole tone scale in “diatonic” triads (I put “diatonic” in quotations because the whole tone scale isn’t a diatonic scale, but the concept for the purpose of practicing is the same). These specific exercises display another interesting thing about the construction of the whole tone scale. If you take two augmented triads a whole step apart, then you have the complete whole tone scale. The third exercise is particularly interesting because it creates a hemiola. This makes the exercise more rhythmically interesting.

This last exercise uses notes outside of the whole tone scale. The fourth note of each four note group acts as a passing tone. You still get the sound of the whole tone scale, but it creates a more interesting line.

Application to Improvisation

As with the diminished scale, the whole tone scale can be applied to any dominant chord. The key is using your ear. The rhythm section can choose to alter any dominant chord to have a sharp five. As a soloist, you can imply the whole tone sound and the rhythm section should hear it and respond.

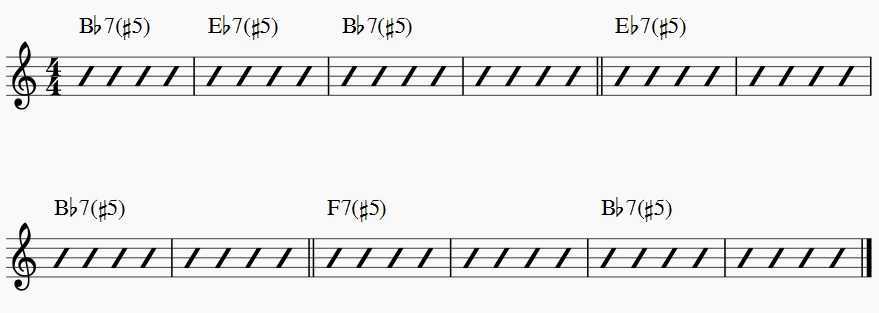

A good way to practice applying this scale to improvising is to practice it over a blues piece. The twelve bar blues progression in its simplest form is comprised of all dominant chords. I would suggest practicing a bunch of whole tone exercises over blues to get the sound into your ear. A harmonically altered version of the blues progression you can practice over would look something like:

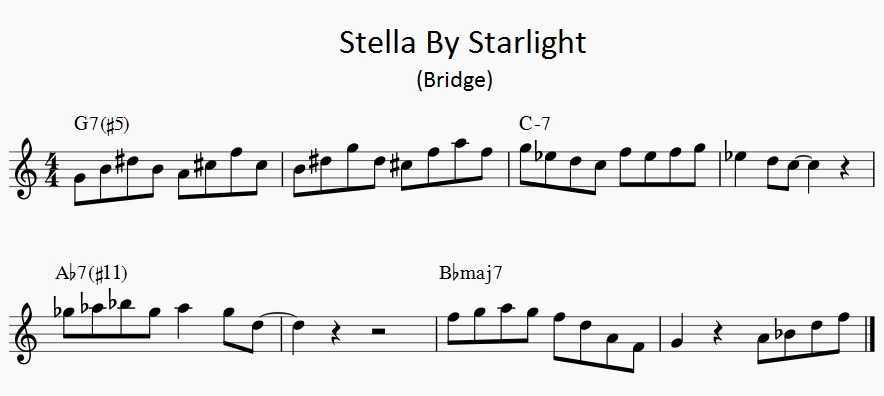

Also, there’s a very popular jazz standard called “Stella By Starlight” that specifically uses a dominant seventh with a sharp five chord. The first chord of the bridge (bar 17 of the form) is especially striking because of this, and it’s the perfect place to use the whole tone scale. I’ve written out a sample solo over the bridge. The first two bars use one of the whole tone exercises from above.

Conclusion

The whole tone scale is an important part of music. It has a very recognizable sound. Also, it’s not too difficult to learn. There are only two scales and they lay well on pretty much every instrument. As always, this blog post is meant to be a brief introduction. There are plenty of excellent educational resources available that delve deeper into all things concerning the whole tone scale. Enjoy practicing. Next article will be about the altered scale (diminished whole tone scale).