“Autumn Leaves” is one of those standards that everyone knows. It’s one of the first standards that every jazz student learns. If you only know ten jazz tunes, you probably know “Autumn Leaves”. If you only know five jazz tunes, you still probably know “Autumn Leaves”. If you’re at a jam session and someone calls “Autumn Leaves”, you better know it. If you search google for “must know jazz tunes”, there may be some variation on what tunes people think are important to know, but every one of those lists will have the blues, rhythm changes, and “Autumn Leaves”.

There are so many definitive recordings of “Autumn Leaves”. A quick YouTube search will find you recordings by artists as diverse as Stan Getz, John Coltrane, Chet Baker, Nat King Cole, Barbara Streisand, Eric Clapton, etc. But no recording of “Autumn Leaves” is as definitive as Cannonball Adderley’s recording from his album entitled “Somethin’ Else”. I highly suggest you check that recording out if you haven’t already. And learn the introduction.

I remember learning and improvising over “Autumn Leaves” in high school. I can remember a specific instance of recording myself soloing over the changes. I wish I could find that recording to listen to today. At that specific time in my learning process, I didn’t understand jazz from a theoretical standpoint. I treated each chord as its own entity; self-contained. Each word as its own, not part of a sentence. For example, instead of seeing the first four bars as a common ii-V-I-IV progression, I simply saw a C-7 chord followed by an F7 chord followed by a Bbmaj7 and then an Ebmaj7. I’m curious to hear what that sounded like. It probably sounded pretty choppy and phrase-less. If you’ve read most or all of my blog posts so far, you should be well ahead of where I was at that time. If you still have some questions, hopefully this article will clarify a few things.

Becoming Familiar with the Progression

We’ve gone over the process of becoming familiar with a given progression, applying previously practiced material to it, and learning to play a cohesive solo over that progression a couple of times now. We’ve worked out the process over the blues progression as well as over rhythm changes. To be completely thorough, though, I thought it would be a good idea to go over the process using a popular jazz standard.

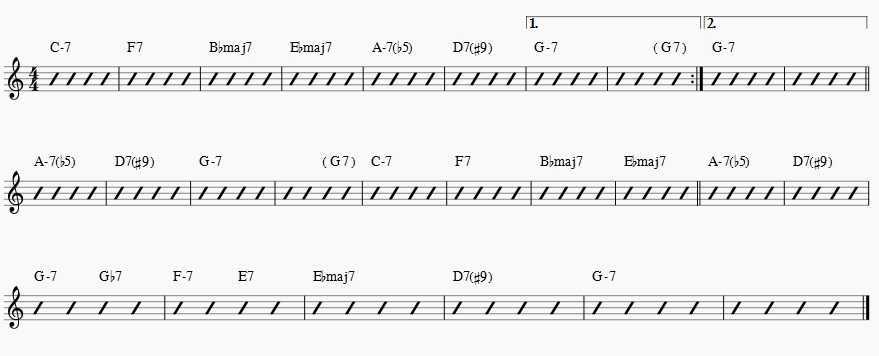

The form and harmony of “Autumn Leaves” is relatively simple. The musical form can be analyzed as AABC, with each section being eight bars. The ‘A’ sections are simply a ii-V-I in a major key followed by a ii-V-i in the relative minor key. The ‘B’ section does the exact same thing, except backwards (it starts in the minor key and then goes to the relative major key). The ‘C’ section gets slightly more complicated, but not by much. The ‘C’ section modulates to the key of IV through a step-down progression before making its way right back to the minor.

The melody is also worth mentioning. I didn’t talk about melody when going over the blues and rhythm changes, because they are progressions that have several possible melodies. I feel the need, though, to stress the importance of learning a melody. Some could argue that the melody is the most important part of playing a jazz tune. When improvising over a song, the majority of people listening will have no idea what you’re doing. But, they will know when you’re playing the melody. To truly master a song, you should learn the words to the melody. There will always be somebody in the audience that knows every word to the song you’re playing. If what that person is singing in his or her head is different from what you’re playing, he or she will notice. You could improvise the greatest solo ever played, but your solo will be tainted if you screw up the melody. The melody to “Autumn Leaves” is singable and full of sequences.

Because of the simple form, harmony, and melody, “Autumn Leaves” is one of the easier tunes to learn in twelve keys. If you’re looking for a challenge, it would be beneficial to learn to play and solo over “Autumn Leaves” in all of the keys. Singers do this one often, so it’s not like the work will be for nothing. The two most common keys are G minor (the original) and E minor (real book key).

Now that we’ve analyzed “Autumn Leaves” so that the progression makes sense to us logically, it’s time to practice the progression so that it makes sense in our ears and under our fingers. You should become familiar with the progression by listening to a bunch of recordings (some of which I listed above), listening to a play-along until the progression sounds familiar, and learning it on piano or guitar.

Once you’ve done that, it’s time to apply some digital patterns. For the following exercises, I’ll just use the ‘A’ sections, though you should apply all of the same concepts to the complete form.

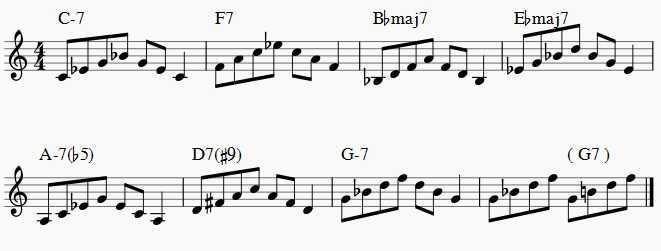

As per usual, we’ll start by applying a strict digital pattern. I chose to use 1357531 as an example. You should also apply a bunch of other digital patterns you’ve worked on (1235, 1357, 1325, 1537, 7531, etc.)

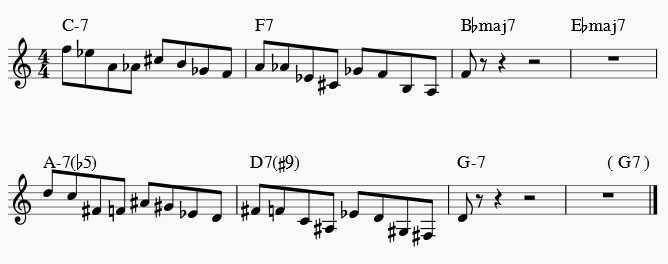

After you’ve practiced some digital patterns and feel comfortable, you can start being a little more creative. Last time, we went over something called a “chord tone solo”. A “chord tone solo” is improvising using only the four notes of the given chord (usually 1357). Basically, the idea is to be creative, but set certain limitations so your focus shifts to working on specific things. When you set limitations, you’ll get better at targeted things so you’ll come out with more varied strategies when no limitations are set. The example I wrote out utilizes all eighth notes. The next step would be to vary your improvisation rhythmically.

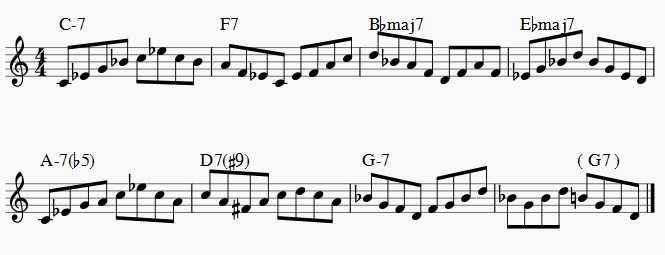

This example uses only chord tones and sets another limitation: keeping your solo within one octave (C-C). Again, once you’re comfortable with this exercise, you can vary your solo rhythmically, as well as set new limitations or remove existing ones.

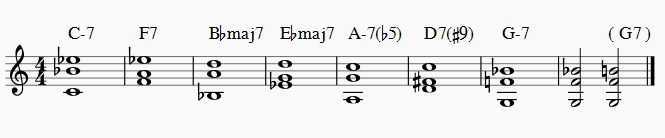

This example shows the common resolutions in the first eight bars. The bottom notes are the roots of the chord, the middle notes are the 7-3 resolutions, and the top notes are the 3-7 resolutions. The point of this example is to show how you can have the least amount of movement between chords in order to create a melodic solo. A way to utilize this in your practice session is to put a play-along on, play through the resolutions using whole notes (as in the example), then try playing through the resolutions using half notes, quarter notes, eighth notes, etc. This will create a smooth, melodic improvisation, contrasting the more chordal-based method of using a chord tone solo.

Applying Scales, Patterns, etc.

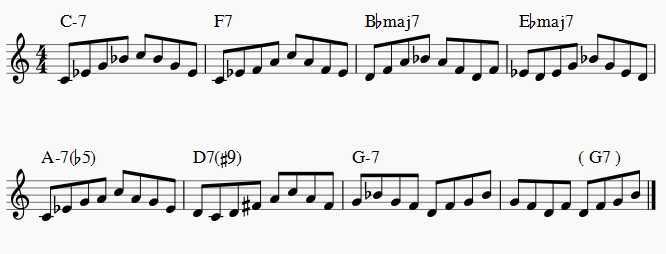

After you’re familiar with the sound of the chord progression while soloing over “Autumn Leaves” using only chord tones, you can apply some altered tones. The first step is to play the altered scales through straight (as we did with the digital patterns) to get the new sounds in your ear.

Following that, you can apply some patterns you’ve been working on utilizing the scales.

Diminished Scale:

Altered Scale:

Creating a Cohesive Solo

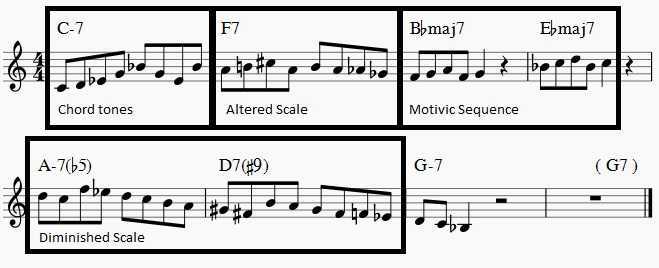

Once you feel comfortable with all the exercises above, it’s time to create a cohesive solo. You should write out some choruses as well as experiment just improvising. The following example is an exercise I wrote out using the various methods we’ve been working on.

Conclusion

Now we’ve gone through a systematic approach to improvising using three different tunes: the blues, rhythm changes, and “Autumn Leaves”. The same approach should be applied to every tune you work on. This is by no means a comprehensive approach. There are tons of other ways tunes can be practiced. Some of these other ways are mentioned above. You can set different limitations. There are virtually infinite limitations you can set. You can say you’re going improvise a solo using only one note or one scale. You can improvise using the same rhythm repeated over and over again. You can improvise using a “play two bars, rest two bars” approach. The process of learning and practicing improvisation is endless. That’s what makes jazz so fulfilling. It’s a lifelong pursuit. There are always new things to practice. Hopefully these past few articles have laid the groundwork and inspire you to practice.

Thanks

Actually fantastic music understanding above. Lovely how you explain. I could add that following the chord progression in a solo is sounding great apart from what scales are in play. Using sixth and second along with chord progression and then all the traditional Am blues scale and some diatonic add ins is how I play it – but I'm not that famous ;)

Hi Chris,

I just recently got back into playing tenor after 20 years. I’ve been struggling with how to improvise over chord changes, and like you wrote, I was trying to figure out how to play “by chord.” I sound completely choppy and like I have no idea how to make the phrasing flow together naturally. What you wrote struck a major chord (lol – pun intended)! I am working on improvising over the Beatrice backing track on my irealpro app and can’t wait to try out your methods. This is awesome