Concert pitch is a strange thing. Many professional musicians will spend their entire careers never having to deal with concert pitch. At the same time, eighth graders all around the world have to deal with concert pitch on a regular basis.

Concert pitch refers to the universal standard pitch, A=440hz. Music has an extremely complex history. And now transposing instruments exist. Not all Cs are the same. In an orchestra, if the director asks the string instruments to play a C major scale, everyone (violins, violas, cellos, basses) plays a C major scale. Simple. In a concert band, if the director asks the same thing, the flutes and trombones do play their C scale, but the clarinets and trumpets play their D scale, the alto saxophones play their A scale, the French horns play their G scale… Not so simple.

Reasons for Concert Pitch

So now you know what concert pitch is. I’m betting your first thought was something along the lines of: “Why does concert pitch exist? Why is it a thing? What’s the point?”

So now you know what concert pitch is. I’m betting your first thought was something along the lines of: “Why does concert pitch exist? Why is it a thing? What’s the point?”

As mentioned above, the history of music is incredibly complex. No one sat down and planned out all of the complexities of music; how music was going to work. Music varies greatly from culture to culture. When we talk about music in our culture, we are referring to Western art music; music developed through European art traditions. Music, to us, is defined by intervals at the half step, time signatures in which 4/4 is the most common, the major scale and the minor scales, etc. Other cultures have different understandings and defining characteristics of music.

To get a little philosophical, nothing isn’t and then all of the sudden is. Nothing appears out of thin air. As with everything in life, music developed through a gradual evolution. And evolution isn’t perfect. Things adapt, but they remain imperfect.

I’m getting a little off topic here. In terms of the content of this article, chromatcism was not always possible on instruments. A great example is the flute. Consider the history of the flute. For a long time, flutes were diatonic instruments in many cultures. To play in a different key, you would need to play a different flute.

But, now it is possible to pitch every instrument to C. The technology exists. Why don’t we simply change every instrument to a non-transposing instrument? Hopefully this hypothetical question sounds completely ridiculous to you. There are many reasons why this wouldn’t be plausible. Technically, it would be possible, but it wouldn’t be at all practical. First of all, it would basically involve rewriting history, figuratively and literally. Instruments have been perfected in the respective keys that they are in. Companies have been improving upon instruments over a long period of time. Each instrument has its defining tonal qualities that couldn’t possibly be replicated. Look at the C melody saxophone. It was an attempt to reinvent the saxophone as a C instrument. It didn’t last long. Also, look at the clarinet. You might wonder why there’s a clarinet in Bb and a clarinet in A. They have different tonal qualities and so both remain a part of modern music. Changing all instruments to be pitched in C would also involve a literal rewriting of all music written for transposing instruments; infinite hours spent rewriting music’s repertoire. All of the great orchestral repertoire was written for instruments that exist. Changing that would mean changing the composer’s intent. Additionally, pitching every instrument to C would mean instruments could only transpose at the octave. It’s more practical to have instruments in between. Think of the difference between the piccolo and the flute, or the difference between the alto saxophone and the baritone saxophone. That’s what an octave transposition looks like. The alternative would be having the same fingering on the alto and tenor saxophone be thought of as a different note. The reason saxophones are in Bb and Eb is so that the fingerings are the same on each saxophone, even though the notes produced sound different.

Anyway, you can see that the idea of concert pitch is ingrained in a complex history. Changing that would mean changing the very foundation of music. It would be complex, to say the least. It would mean altering the past, present, and future of music. Think about it this way: which is easier, the slight learning curve of having to learn to transpose or completely reinventing everything about music? That’s why concert pitch still exists and will continue to exist.

Who Should Know Concert Pitch?

Who should know concert pitch? Or rather, who benefits from understanding concert pitch? There are different levels of understanding concert pitch. If you play a transposing instrument, you probably know what “concert Bb” is without hesitation. Someone tells you to play a concert Bb major scale, and you can do it without even thinking. But, could you read a concert pitch lead sheet on your instrument?

Having a deep understanding of concert pitch can benefit any musician. Composers and arrangers should be pretty fluent in instruments ranges, transpositions, timbres, effects, etc. Band and orchestra conductors should have a thorough understanding of transposition. Many times, conductors are reading from concert pitch scores. Knowing how to transpose all of the instrumental parts allows them to communicate more effectively with the members of the ensemble. Accompanists are sometimes asked to reduce a score to a piano part. The ability to read an orchestral score on the piano is a very good skill to have. If you’re a jazz player and you play a transposing instrument, you will likely be expected to read concert pitch lead sheets. Many times, the piano player or bass player will bring in music, but have every part written out in concert pitch. Or they’ll want to play a tune you don’t know but they only have the C Real Book. These happen to me all the time. As an alto sax player, I’ve become completely fluent reading concert pitch lead sheets.

Instrument Transpositions

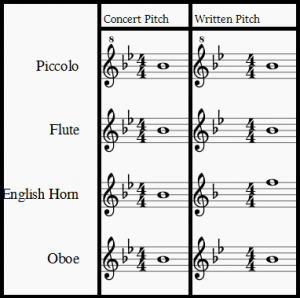

There are many non-transposing instruments, instruments where concert pitch and written pitch are the same. Violin, viola, cello, flute, oboe, bassoon, trombone, etc. all play in concert pitch.

Some instruments transpose at the octave. The double bass sounds one octave lower than its written pitch. The piccolo sounds one octave higher than its written pitch. But, if you want to hear a C, and you don’t care what octave it’s in, then the double bass and piccolo play their C.

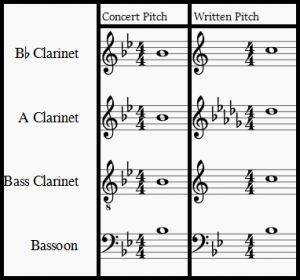

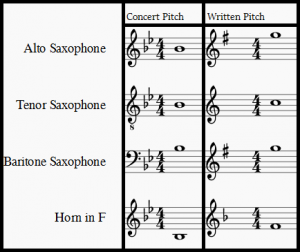

Trumpet, tenor sax, and clarinet are Bb instruments. This means when they play their written C, it sounds like a Bb in concert pitch. Alto sax, bari sax, and clarinet in Eb are Eb instruments. When they play their C, it sounds like an Eb. English horn and French horn are pitched in F. There are also instruments pitched in G, A, D, etc.

I’ve made some charts of the most common band instruments and their transpositions. The first column is “concert pitch” and the second is “written pitch”. When your director asks the band to play a concert Bb, this chart shows what note each instrument would play.

Conclusion

The famous jazz and avant-garde musician Ornette Coleman developed a musical concept called “harmolodics”. An extremely intricate philosophy, part of it applies to transposing instruments. In theory and in practice, Ornette Coleman believed that harmony and harmonic direction were determined by a melody’s overall shape and movement. Therefore, transposing, as part of his overall concept, is unnecessary. In other words, concert pitch becomes irrelevant. Everyone can read from a concert pitch lead sheet. If you have a piano, trumpet, and alto saxophone all reading the same melody, each instrument would be playing a different note, but the overall direction would remain constant.

From the 1910s to the early 1930s, the C melody saxophone was a fad of sorts. It was marketed as a saxophone that you could use to read over a piano player’s shoulders without needing to transpose. It was the perfect layman’s saxophone. It never fully caught on, though. It was a failed effort to reinvent the saxophone to make it easier to play. But, the alto, tenor, soprano, and baritone saxophones were firmly established. The C melody saxophone just didn’t sound as good, so the idea was abandoned. In music, sound is everything; sound comes first and foremost, over ease of use.

Concert pitch is an aspect of music that is thoroughly ingrained, weaved deep into its foundation. It’s not as difficult of a concept as it might seem at first. Like I said, I can read concert pitch lead sheets on my alto sax with complete fluency. I know a lot of musicians that can’t do this, and they do just fine in most situations. However, knowing concert pitch and being able to transpose is a good skill that I believe will make you a better musician.