In 1943, while the classical music and animation communities were still buzzing about Walt Disney’s Fantasia, Warner Bros. decided to tilt that conversation in their favor; they began to release animated shorts parodying Fantasia’s use of classical music.

In 1943, while the classical music and animation communities were still buzzing about Walt Disney’s Fantasia, Warner Bros. decided to tilt that conversation in their favor; they began to release animated shorts parodying Fantasia’s use of classical music.

First came Corny Concerto and Pigs in a Polka in 1943, followed Michael Maltese’s Herr Meets “Hare” in 1945. Rabbit of Seville (directed by Chuck Jones) remains one of the most popular Warner Bros. cartoons of all time.

By focusing on parody rather than pomp, Warner Bros. was onto something that would, in fact, change the conversation.

As the classical-music-in-cartoons conversation shifted towards comedy, so did the entire face of Warner Bros–and two men in particular, Chuck Jones and Michael Maltese, rose to the surface.

Who is Chuck Jones?

Have you seen the Disney-produced masterpiece, Fantasia (1940)? That ground-breaking work featured seven classical pieces of music, each performed by the Philadelphia Orchestra and conducted by Leopold Stokowski. It was serious, beautiful, and artistic.

Ironically, Disney’s grave use of classical music may have been the spark plug that ignited Warner Bros.’ classical music parodies. Chuck Jones enjoyed a rivalry with Disney Studios; Chuck likely composed his first operatic cartoon, “Rabbit of Seville,” to thumb his nose at Disney.

“There’s no doubt Chuck Jones teases classical music. It’s high-falutin’, and Bugs isn’t that,” says William Gadea, founder of Idea Rocket Animation in NYC.

The Warner Bros. cartoons certainly weren’t devoid of artistic feeling, though. “When Bugs conducts in Long-Haired Hare and Baton Bunny, he really feels the music! It’s genuine,” adds Gadea.

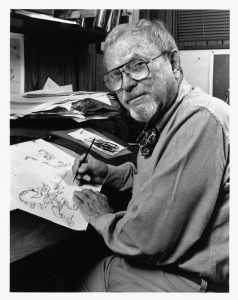

If you’re familiar with Wile E. Coyote, Pepe le Pew, Elmer Fudd, Marvin the Martian, or Michigan J. Frog, then you’ll recognize the sharp wit and endless creativity of Chuck Jones. He burst onto the animation scene in the 1930s with Leon Schlesinger Productions—Schlesinger produced Looney Tunes—before continuing with the company after Schlesinger sold to Warner Bros.

During WWII, Chuck Jones worked with Theodor Geisel, aka “Dr. Seuss,” eventually collaborating on the animated “How the Grinch Stole Christmas.” But despite Jones’ many accomplishments, we’re interested in his use of classical music–we’ll get to that right after we discuss the next classical music “guru” at Warner Bros., Michael Maltese.

Who is Michael Maltese?

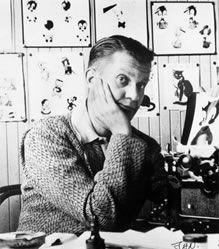

The year 1940 brought about a classic Warner Bros. cartoon, You Ought to be in Pictures. While that picture probably isn’t top-of-mind, you might remember the live-action guard who has to chase Porky Pig.

That was acclaimed animation screenwriter Michael Maltese.

Maltese wasn’t a live-action actor by trade; he started screenwriting for Schlesinger Productions (later Warner Bros.) in 1941, and later worked with Chuck Jones.

When it comes to pairing classical music with animation, Maltese actually beat Chuck Jones to the punch.

Show Me the Cartoons

Michael Maltese started working with the classical music/cartoon hybrid before Chuck Jones, and the two visionaries eventually came together to produce some of the industry’s most notable projects.

Here is a chronological list of the greatest classical music-related cartoons involving Chuck Jones, Michael Maltese, or both. Some of the links take you to full showings, but due to copyright laws, some of them lead to Amazon or short clips. Sorry!

1941: Rhapsody in Rivets

Written by: Michael Maltese

Rhapsody in Rivets, directed by Warner Bros. fixture Friz Freleng, used Hungarian Rhapsody No. 2 by Franz Liszt as its musical foundation. The cartoon focused on a group of construction workers making music with their various tools and machines.

Rhapsody in Rivets, directed by Warner Bros. fixture Friz Freleng, used Hungarian Rhapsody No. 2 by Franz Liszt as its musical foundation. The cartoon focused on a group of construction workers making music with their various tools and machines.

Rhapsody in Rivets was nominated for an Academy Award, although it ultimately lost to Lend a Paw from Disney.

Unfortunately, you can’t find this cartoon on YouTube; you can buy it for $10 (as part of a collection) on Amazon, though.

1945: Herr Meets Hare

Written by: Michael Maltese

This Warner Bros. cartoon, in which Bugs visits Germany, was released shortly before the end of World War II, and like Rhapsody in Rivets, it was directed by Friz Freleng. Composer Carl Stalling featured the music of Offenbach, Strauss, and Wagner, thus continuing Warner Bros.’ connection to classical music.

You can listen to this one on Youtube, although the quality is awful due to licensing issues. You might be better off buying Herr Meets Hare here.

1946: Rhapsody Rabbit

Written by: Michael Maltese

Maltese wrote Rhapsody Rabbit as a kind of sequel to Rhapsody in Rivets — both stories focus on a performance of Liszt’s Hungarian Rhapsody No. 2. In Rhapsody in Rivets, construction workers perform the theme with their various tools, in the 1946 “sequel,” Bugs performs the piece from a concert stage (for comedic effect, of course).

Maltese wrote Rhapsody Rabbit as a kind of sequel to Rhapsody in Rivets — both stories focus on a performance of Liszt’s Hungarian Rhapsody No. 2. In Rhapsody in Rivets, construction workers perform the theme with their various tools, in the 1946 “sequel,” Bugs performs the piece from a concert stage (for comedic effect, of course).

MGM actually released The Cat Concerto around the same time, and it also focused on Hungarian Rhapsody No. 2. Major controversy ensued. So which studio had the idea first? Was it Tom and Jerry or Warner Bros.? We may never know, but MGM did win an academy award for their short film, while Warner Bros. left empty handed.

You may have to hand over $.99 to watch this full episode on Youtube.

1949: The Long-Haired Hare

Directed by: Chuck Jones

Written by: Michael Maltese (see below for bio)

Chuck Jones’ first foray into classical music was an overt jab at Disney for two reasons in particular:

- Firstly, the term “Longhair” has been used as a playful reference to someone with intellectual music taste (in this case, classical music).

- And secondly, the cartoon presents a humorous depiction of Leopold Stokowski—the conductor featured in Disney’s Fantasia.

As far as the actual music is concerned, Carl Stalling orchestrated arrangements of Rossini, Donizetti, Wagner, and Suppé.

In this clip you can clearly see Chuck Jones having fun at Leopold Stokowski’s expense–and it’s wonderful. View it here

1950: Rabbit of Seville

Directed by: Chuck Jones

Written by: Michael Maltese

According to Chris Higgins of Mental Floss, “While you watch, note the number of fingers Bugs Bunny has. He’s traditionally drawn with three fingers and a thumb on each hand, but in one shot at 6:17 (where he’s “playing piano” on Elmer’s head), Bugs suddenly has full human hands.”

That’s just one of the many funny moments in this classic Warner Bros. take on The Barber of Seville.

Rabbit of Seville centers on Bugs Bunny joining a production of The Barber of Seville inside the Hollywood Bowl. Hilarity ensues. The short has been voted #12 on an industry list of The 50 Greatest Cartoons.

Here’s a video of a live performance/showing of the cartoon (for copyright reasons):

1957: What’s Opera, Doc?

Directed by: Chuck Jones

Written by: Michael Maltese

“[Chuck Jones’] own favorite among all his shorts was What’s Opera, Doc?, says William Gadea of Idea Rocket. “It’s supposed be Wagner’s Ring Cycle compressed into seven minutes, but it borrows from some other Wagner operas as well.”

Specifically, Carl Stalling borrowed from Der Fliegende Holländer and Wagner’s Tannhäuser.

What’s Opera, Doc? ranked #1 on the list of The 50 Greatest Cartoons. Here’s another video of a live performance in Hollywood:

1959: Baton Bunny

Directed by: Chuck Jones

Written by: Michael Maltese

This cartoon features Bugs Bunny as a conductor, and the classical work for the program is Franz von Suppé’s Ein Morgen, ein Mittag und Abend in Wien.

Here’s an excerpt:

1976: Bugs and Daffy’s Carnival of the Animals

Directed by: Chuck Jones

Carnival of the Animals was one of the only classical music-inspired cartoons by Chuck Jones for which Michael Maltese did not write the story; this plot came from Jones himself.

It was based on the musical work of the same name by Camille Saint-Saëns and poetry by Ogden Nash. CBS aired this episode during prime-time–an obvious nod to Chuck Jones’ loyal adult following.

Watch sections of it here:

Chuck Jones’ and Michael Maltese’s Classical Music Legacy

“Of course, these pieces can’t be fully appreciated when heard out of context, or in commercials and cartoons,” said Gadea. “But they are stepping stones across the river, until you don’t mind getting wet in the music. When all’s said and done, I think Bugs (and Chuck!) has been great for opera.”

Even if Chuck Jones initially used classical music as a method to mock Disney, his love for the genre eventually broke through.

Modern Americans often equate “The Barber of Seville” with Bugs Bunny; for better or for worse, Chuck Jones is the gateway between cartoon enthusiasts and opera.

*Silly Symphonies didn’t use classical music, as the scores were created by Curt Stalling. However, the instrumentation and “symphonic” aspects of the series led to Fantasia’s creation.