The Augmented Scale

Last time, we talked about the blues scale and how it is often the first “jazz” scale taught to young musicians. When you search for information about the blues scale on the internet, you end up finding more information (good and bad) than you would ever know what to do with. The augmented scale, not so much. I mean, there are resources available, just not as many as are available about the blues scale. I guess this can be a good thing.

I remember first being introduced to the augmented scale in college and not knowing what to do with it. It’s a weird thing being taught a scale and then being told to figure out how to apply it. Applying the diminished scale, the whole tone scale, the altered scale, the blues scale, etc. is pretty straightforward. The augmented scale is not as clear cut. Maybe this is why it’s not taught so much, or why it’s taught at a later stage in a player’s development.

I guess I could go as far as to say that the augmented scale is not the most useful scale. When you look for examples of professional jazz musicians using the augmented scale in their improvised solos, you only really come up with a handful of examples. Why study the augmented scale then? To me, the augmented scale is one of the most interesting scales there is. And, why do we study music anyway? Is it a competition to see who can be the best at improvising? If that’s your way of looking at it, you won’t last very long. We study music because it is creatively and intellectually rewarding. The augmented scale is a fun scale to study.

Scale Construction

When we went over the diminished and whole tone scales, I introduced the concept of symmetric scales. There are four symmetric scales: the diminished scale, the whole tone scale, the chromatic scale, and the augmented scale. The augmented scale is definitely the least studied symmetric scale. Symmetric scales are called such because they have repeated intervals or groups of intervals. The chromatic scale is repeated half steps, the whole tone scale is repeated whole steps, the diminished scale consists of a half step and then a whole step (or a whole step and then a half step) repeated. The augmented scale consists of a minor third followed by a half step, repeated.

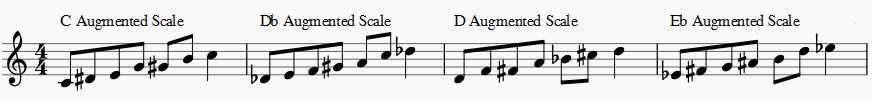

Like the diminished scale and the whole tone scale, the augmented scale has limited transpositions. The augmented scale transposes into four different keys. The scale repeats itself every major third. C, E, and Ab are the same scale; Db, F, and A are the same scale; D, F#, and Bb are the same scale; and Eb, G, and B are the same scale.

Chord/Scale Relationship

One reason the augmented scale is one of the least taught scales is because its application isn’t so clear cut. The diminished scale is played over a diminished seventh chord or a dominant seventh with a sharp or flat nine chord, the whole tone scale is played over a dominant seventh with a sharp five chord, the altered scale is played over an altered chord, the blues scale is based on the key, etc., etc., etc. Even some slightly more obscure scales have clear cut applications: the Lydian augmented scale is used over a major seventh with a sharp five and sharp eleven chord and the Locrian #2 scale is used over a half diminished chord.

The augmented scale’s applications aren’t so obvious. Maybe think of it in terms of a scale you’re familiar with. How do you apply the chromatic scale to improvisation? What chord can you play the chromatic scale over? The answer is and isn’t obvious. The chromatic scale can be played anywhere. It can be played in many situations. The augmented scale works in a similar way. You kind of just have to figure out what chords the notes in the scale would work over. We’ve done this with every other scale I’ve written about already. This time, though, maybe not all the notes will completely fit the chord.

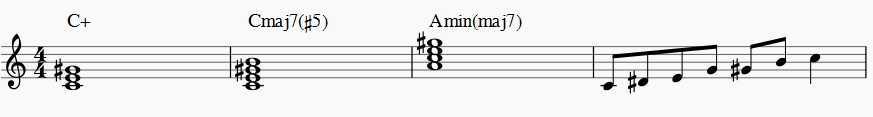

Here are a few chords that the augmented scale works over. The first chord is the most obvious. The augmented scale works over an augmented chord. The scale is simply an augmented chord with a leading tone (or note a half step below) preceding each chord tone. The second chord follows the same logic but counts the last note of the scale as a chord tone. The third chord may be a bit confusing to some because the root of the chord is not in the scale. For the minor (Major7) chord, you think of it as the scale starting on the fifth or the seventh of the chord.

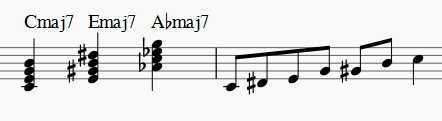

These next two examples start to get into pretty advanced concepts, so I won’t go into too much detail. The augmented scale can be used to imply three tonalities at once. If you are in C Major, you can imply C Major, E Major, and Ab Major. Take a look at the C augmented scale. Within the scale, you have all the notes of a Cmaj7 chord, a Emaj7 chord, and an Abmaj7 chord. By weaving in and out of three tonalities, you create tension and release (which I talked about a bit in the article on the altered scale). This concept of implying three tonalities a major third apart was first introduced by John Coltrane in his compositions “Giant Steps”. Like I said, this is starting to get into pretty advanced territory, so I’ll let you explore it on your own, or maybe I’ll write about it in a later article.

Scale Patterns

As per usual, I’ll provide a few patterns that I like to use in my own playing. I really like the augmented scale. Whenever I practice the augmented scale, I keep figuring out new things about its construction.

This first example focuses on the triads of the three tonalities with a leading tone to the third scale degree. This example also sounds cool as a diminished scale pattern if you use four triads a minor third apart rather than three triads a major third apart.

This second example shows a cool way to think about the scale intervallically. A good way to practice technique is to practice intervals in different intervals. For example: major seconds in half steps, minor thirds in half steps, minor thirds in whole steps, etc. When you practice all these intervals, you begin to see patterns and how different scales are constructed. The whole tone scale, intervallically, is whole steps in major thirds; the diminished scale, intervallically, is whole steps in minor thirds. The augmented scale is minor thirds in major thirds. This example is a way of practicing minor thirds in major thirds.

This third example is the most popular augmented scale pattern. It makes use of the three triads a major third apart.

This fourth and final example is a pattern based on a concept called “triad pairs”. Using triad pairs is popular among jazz musicians. A triad pair consists of two triads that have notes in common. Some examples are: two major triads a half step apart, two major triads a whole step apart, two minor triads a whole step apart, two major triads a tritone apart, etc. This is another advanced jazz concept that I may write about at a later date. The augmented scale can be deconstructed into two augmented triads a minor third apart. This is just another creative way of practicing and utilizing the augmented scale.

Application to Improvisation

Applying the augmented scale to improvisation is a trial and error process. But then again, applying any scale to improvisation should be a trial and error process. You shouldn’t just play a diminished scale over a diminished chord because you know that it works there. It should be a sound in your ear; you should know what it’s going to sound like before it comes out. In order to accomplish this, you need to practice a given scale over different chords and in different situations. You should sit at a piano, play a chord, and play a scale in different permutations over that chord. That’s the only way to get a particular sound in your ear. With the augmented scale, this is even more important, as the application isn’t so cut and dried.

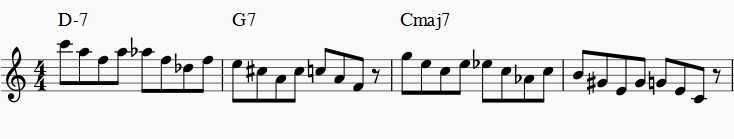

These first three examples show how you can apply the augmented scale to a ii-V7-I progression. Technically the first example is the “correct” version. By “correct”, I mean the most commonly utilized. The augmented scale is three triads a major third apart from each other. So, you’re implying the three tonalities over the seventh chord as well as over the major seventh chord. Over the G7, you’re implying G, B, and Eb. The problem with this is you’re playing a major seven over a dominant seventh chord. Nonetheless, this is the most common use of the augmented scale over a dominant seventh chord. The next two examples show how different, less “correct” augmented scales can be used over the same chord. I left out the fourth version, because it doesn’t sound right to my ears. The major seven shows up too often over a dominant seventh chord. The only way to know what sounds “correct” to you is to practice the different scales over any given chord.

This last example just shows the application of the augmented scale in a minor key. Once again, play this chord on the piano and practice the scale to see if it sounds right to your ears.

Conclusion

Hopefully this post has conveyed my enthusiasm for the augmented scale. You probably won’t find yourself using the augmented scale in every solo you take. But, the point of studying all these different scales isn’t only to transform yourself into the greatest improviser of all time. That could be one goal. We study music because it enriches our minds and our lives. I chose to write about the augmented scale because it’s one of those scales that stands out to me as being unique and interesting. Maybe it’s just me. You’ll probably find other scales more interesting. But that’s the thing about music: everyone has different taste and no one’s taste is necessarily bad.

I said at the beginning that there aren’t as many resources about the augmented scale as there are about the other scales that we’ve talked about. If the augmented scale is interesting to you so far, and you feel like studying further, I recommend “The Augmented Scale in Jazz: A Player’s Guide” by Ramon Ricker and Walt Weiskopf. It’s a pretty definitive resource regarding the augmented scale.