The Blues Scale

Every now and then, I’ll meet a fellow musician, or read an interview with a popular jazz musician, who started listening to jazz practically the moment he or she was born. You hear about musicians whose parents were jazz musicians, or huge fans of jazz, and always had great jazz records playing. Unfortunately, for most people this is not the case. Most of the time, a young jazz musician is first introduced to jazz through their school band program. When this happens, the blues scale is often the first “jazz scale” that the student is taught. Usually it’s the next scale learned after the major and minor scales.

I remember being introduced to the blues scale in jazz band when I was a sixth grader. In some respects, teaching the this scale as the first “jazz scale” makes sense. It’s a one-size-fits-all scale. You can use one single scale over the whole blues progression. But, this methodology can also cause some problems, which is why it’s not the first scale I chose to write about in this series.

What problems can it cause? Being taught that the blues scale can work in many places can lead to overuse and abuse. It can also lead to misconceptions, misunderstandings, and misuse. I remember being a young sixth grader, thinking the blues scale was “the” jazz scale; the main jazz scale that all the great jazz musicians used. I thought all great jazz solos were just clever orderings of the notes in the blues scale. Obviously I didn’t listen to a lot of jazz at the time, or I would’ve quickly figured out that this isn’t the case.

Also, obviously, I’m not the only one who thinks this. I remember sophomore year in college, perusing videos on YouTube with my roommates, as college students do. We found a video of a young saxophone player performing a solo rendition of “Giant Steps” on a beach boardwalk somewhere. We had to check out this young musician playing some of the most complex jazz changes. In the video, the young musician plays the head to “Giant Steps” and then proceeds to improvise using the Bb blues scale. Pretty entertaining to watch, but also kind of disheartening in a way. By the way, if anyone happens to find this video, please send it to me. I haven’t been able to find it since I first watched it eight or so years ago.

Scale Construction

The blues scale doesn’t really fit into any category of scales. It’s not a diatonic scale, not a chromatic scale, doesn’t have modes, isn’t a symmetric scale. It’s kind of in its own category.

There are a couple of ways to think about this scale’s construction. One way is to think of it as a minor pentatonic scale (1, b3, 4, 5, b7) with one note added (b5/#4). Another way is to think of it in context of “blue notes”. It’s kind of hard to explain blue notes aesthetically, but I’m sure you will recognize them when you hear them. When we talk about blue notes, what we’re referring to are the lowered third, the lowered fifth, and the lowered seventh scale degrees. Or at least this is how we notate them in Western harmony, though when some people refer to “blue notes”, they are referring to quarter-tones (which are not common in traditional Western harmony). Think of a guitarist bending a string, a keyboard player using the pitch knob, a saxophone player using his or her embouchure to bend a pitch, a trombone player using his or her slide, etc.

The blues scale consists of 1, b3, #4, 5, and b7. There are twelve unique transpositions.

Chord/Scale Relationship

As I hinted at in the introduction, the blues scale doesn’t really have a chord/scale relationship. There’s no one chord that this scale fits over. You don’t see a Bb7 and play the Bb blues scale, then see an Eb7 and play the Eb blues scale. You can try it and see how it sounds. I guarantee that it won’t sound right to your ears.

Instead of each scale relating to a specific chord, this scale is based on the overall key. Over a Bb blues progression, you would use only the Bb blues scale. The Bb blues scale sounds good over Bb7, Eb7, and F7 if you’re playing a Bb blues. It just blankets the whole progression. Likewise, if you’re playing an F blues, the F blues scale sounds good over F7, Bb7, and C7.

If you’re playing a standard, the blues scale of the key that the standard is in sounds good. Let’s say you’re playing “There Will Never Be Another You” in Eb. Try playing the Eb blues scale over the Ebmaj7 chord or over a Bb7 resolving to Ebmaj7. Let’s say you’re playing “Autumn Leaves” in Gm. You can play the G blues scale over the Gm7 chord at the end of the ‘A’ section.

Scale Patterns

As I stated earlier, this isn’t really a traditional scale. Personally, I don’t approach the blues scale in the same way I approach most other scales. You could practice it in “thirds”, etc. It’s possible. I do it sometimes, but it’s not necessarily practical. You don’t get the blues sound by playing it in “thirds”. You kind of just get the pentatonic sound with a weird added note in there. With the blues scale, you just have to find some lines that work and have a “bluesy” sound.

Here are a few examples of lines that I like:

The first two examples are kind of self-explanatory. The third example makes use of a common performance practice. It sounds cool to play the blues scale and resolve it to the major third (if you’re in a major key). Jazz and blues players do this all the time.

Application to Improvisation

I sort of already went over how to apply the blues scale to improvisation, but I’ll explain it a little more thoroughly to make sure you understand. Like I said, when you apply this scale to improvising on tunes, you use the blues scale based on the key of the song, rather than any specific chord. Figuring out where the scale sounds appropriate is ultimately up to your ears. When a song is in a major key, you use the blues scale based on the name of the major key the song is in (Eb blues scale on “There Will Never Be Another You). Likewise, when a song is in a minor key, you use the scale based on the name of the minor key the song is in (G blues scale on “Autumn Leaves”).

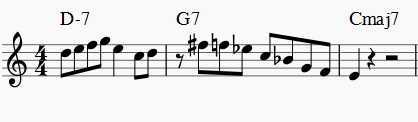

The first example shows how you could use the blues scale over a ii-V7-I in the key of C major:

In this example, I chose to resolve to the major third of C major. You don’t have to. Continuing to play the blues scale would be fine. Even though logic tells you playing the minor third over a major chord would sound bad, it doesn’t really. The context of the blues scale is stronger than the context of the key. As long as you’re confident, the scale will sound good over the major chord.

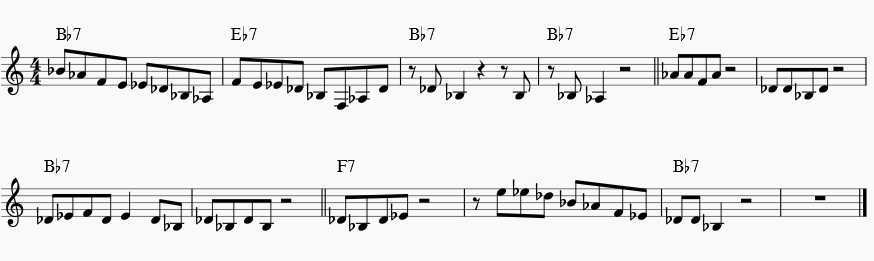

The next example is a Bb blues:

You can use the Bb blues scale over the whole 12-bar Bb blues progression. Here, I chose not to ever resolve the Bb blues scale to the major third, so you can hear how that sounds.

Conclusion

The blues scale is used frequently in several types of music: the blues, jazz, pop, funk, soul/R&B, etc. It has a very familiar sound. In jazz specifically, it’s a useful scale, but it is not “the” defining jazz scale as many are taught when first introduced to jazz. As you become more and more familiar with jazz, you’ll figure out which musicians use the blues scale more than others, what periods it was more popular during, etc. For example, Stanley Turrentine was a saxophone player who used the blues scale liberally. Take a listen to some of his music.

I should mention that sometimes people talk about multiple blues scales (i.e. major and minor). The one I wrote about here is the most common blues scale, and to some people the only blues scale. I just wanted to mention this, just in case you ever run into anyone talking about multiple blues scales. But this should be more than enough to think about for now